What Is STAGE?

Mission

Exploratory Focus

Work Process

History

Participants in all STAGE projects include scientists, engineers, technology/media experts, professional artists (e.g., actors, directors, writers, dramaturgs, cinematographers, editors, as well as set, lighting, sound, projection, and costume designers), and talented students from all disciplines. Projects are developed through brainstorming and improvisation.

Work begins on a theatre project by choosing a scientific topic of particular interest. Then we look for the emotional essence, i.e., metaphors for the science. We construct a personal story based on that essential quality — a story that has an emotional parallel to the science. We then integrate the science story and the personal story throughout the development process.

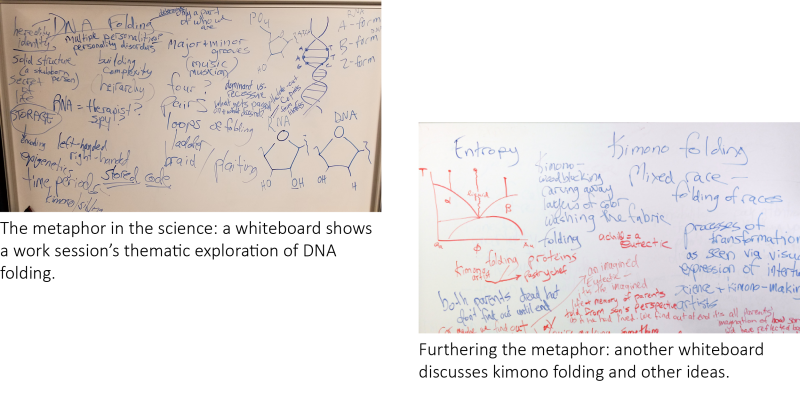

This can be best exemplified by a project currently underway in the STAGE Lab, where a group of graduate and undergraduate students from science, engineering and the humanities are developing a new theatre piece about DNA packaging, or folding. After that topic was chosen, metaphors for DNA were identified: the passing down of traits, identity, who we are. These are ideas that easily lend themselves to a story. The metaphor extends further: the very complex and specific way in which DNA folds in a particular cell type plays a crucial role, ultimately, in how that cell will function. The same can be said of our identities — they're very complex, very specific, and have a great deal to do with how we function.

Once the topic and metaphors are identified, and before improvisations begin, everyone in the room is armed with laptops and books, researching and brainstorming, which continues throughout the process. The participants bring in all sorts of resources to fuel the discussions and around which actors improvise. A resource can be anything — a research paper (which provided the idea of DNA folding), a newspaper article, a film clip, a photograph, a personal anecdote — as long as it has something to do with the topic at hand or is connected to our research or discussions in some way. Thus, in the same project, a few brainstorming sessions centered around finding metaphors for the process of folding: folding clothes to pack a suitcase, folding laundry, folding pastry dough, etc. One of the graduate students offered up the resource of kimono folding, or, more accurately, kimono dressing. The student explained that learning how to dress in a kimono is an art form that involves many intricate steps of folding and tying, and often requires a licensed, professional kimono dresser to assist. Kimonos are passed down from generation to generation and typically never altered, meaning the garment will be folded up and tied in place to make it fit the body of whomever inherits it. Based on these ideas, the group is now in the midst of creating a story about DNA folding that is integrated into a complex personal story of Japanese identity, heritage, and culture.

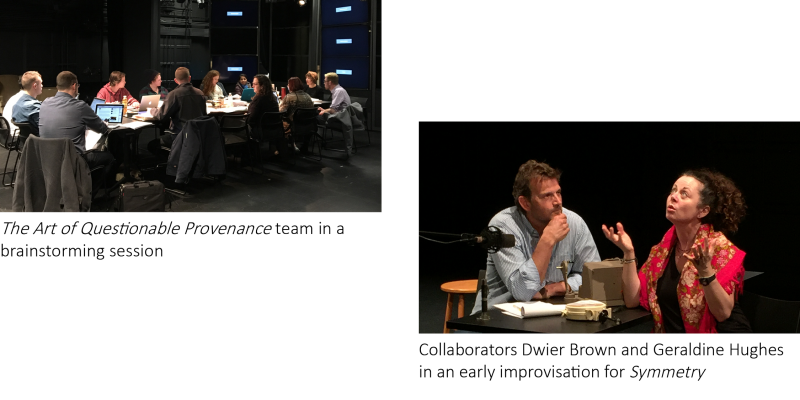

Key aspects of the work process are directly inspired by the exploratory process of experimental science. Each improvisation is akin to running an experiment, i.e., we use the improvisation to generate and investigate new ideas, with continuous analysis and feedback. We constantly weigh and examine what each improvisation reveals, and, just as scientists analyze their results and use that information to revise an experiment, we adjust the circumstances of a scenario and improvise again. As in the scientific process, failure is embraced as a critical component of our work process. Projects are developed over one-to-two years, affording ample time and space for experimentation and research. As in experimental science, intuition plays a key role in the creative process. Collaborators give over to the process itself and follow where it takes them, instead of determining in advance where the process should go. Discoveries that we make along the way sometimes leads to changing course in the middle of a project's development. We focus on what is revealed through the work process itself, and let the most powerful material that emerges guide the creation of the script and the public performances.

Throughout this iterative process, all improvisations are archived by recording them on video — the analogue of a scientist's lab book. We use the improvised material to eventually create our script. In the traditional theatrical process, the script, and costume and set designs, are nearly or completely in place before rehearsals start. Public performances begin 4-6 weeks after the first rehearsal; in contrast to the process of experimental science, there is not adequate time or room for mistakes or discovery. Having a final script in advance of a rehearsal seems rather like a scientist publishing a paper before doing the experiment. This statement is not a dismissal of the traditional theatrical process, but it is further evidence of how the creative process of artistic practice can benefit from the creative process of scientific practice.

In the STAGE Lab, everyone collaborates in the same room, at the same time, from the very beginning — everyone from scientists and writers to actors and multimedia artists. We believe the sum is greater than any of its individual elements. Suppose, for example, the lighting designer is improvising along with the actors, and at one point, in response to what the actors are doing, the lighting designer instinctively throws a panel of light onto the stage. It falls in such a way as to suggest a doorway. Let us say the project we're working on at that moment is about symmetry, so the scientists suggest we have two doorways, one on each side of the stage. Picking up on that idea, the director decides that every time a character enters the door on stage left, another character enters the door on stage right. In this way, symmetry is echoed, and therefore the story is being told on yet another level. This would likely never have happened if the scientists and the lighting designer hadn't been there at just that moment, collaborating together. Everyone's intuition comes into play, and by being exposed to each other's processes, scientists and artists learn to think and work in new ways.

As mentioned, technology is used in the staging of our plays as a critical component of telling the story. We can only see what works by experimenting with different types of technology and media. For example, as we were working on a play about the science of consciousness, one of our graduate student collaborators decided to use Google Deep Dream software to realize the video imagery for a particular scene. He used this software to train an artificial neural network to recognize features and patterns in an image. Specifically, he trained the network to recognize the forms and patterns of butterflies, and then to overemphasize them in the resulting images. By applying this technique to every frame of the video, he was able to create smooth image transitions that replicate the way our attention shifts in dreams. We strongly favor using this kind of technology in the production because it employs an artificial neural network to convey the workings of the brain's neural network, thereby echoing the theme of the play on multiple levels. Moreover, the video that results from using this technology has the advantage of looking especially dreamlike, thereby further enhancing the theme. To give additional thematic resonance, the graduate student chose the imagery of butterflies because in Greek, "psyche" means butterfly, and psyche, in all its meanings, was an important thematic element in this play about consciousness.

Our way of working also raises new questions. With technology integrated into stage performances, will we arrive at a new art form that centers on conveying a story, that is, something that lies between live theatre and the technology of the moving image? Might we come up with new technologies that arise out of the needs of a particular project? Might artistic practice lead a scientist to new ideas, or a new way of doing science — and vice versa?